Procedural paranoia describes a perceived reluctance by Tribunals to act decisively in certain situations for fear of their award being later challenged.

Tribunals have certainly been even more tested than before during the pandemic, with some counsels and parties displaying endless imagination (or a twisted mind?) to deploy new guerilla tactics and set new procedural traps. Some say that those new tactics are here to stay.

On the other hand, a number of leading arbitrators, arbitral institutions, and practitioners have been praised for their reactiveness and their ability to come up with pragmatic and/or innovative solutions.

Where does this leave us? And perhaps even more importantly, what lies ahead?

Is the vaccine in sight? Or shall we rather expect this disease to spread further in the coming months and years?

Experience counsels and arbitrators, and the representative of a leading arbitral institution, will share their views, forecast - and war stories - during what promises to be a lively debate.

On 26 May 2021 the CIArb London Branch and the CIArb Egypt Branch in cooperation with the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA) held a joint online event on the topic of ‘Procedural paranoia in International Arbitration: Is the vaccine in sight or shall we expect the disease to spread further?’

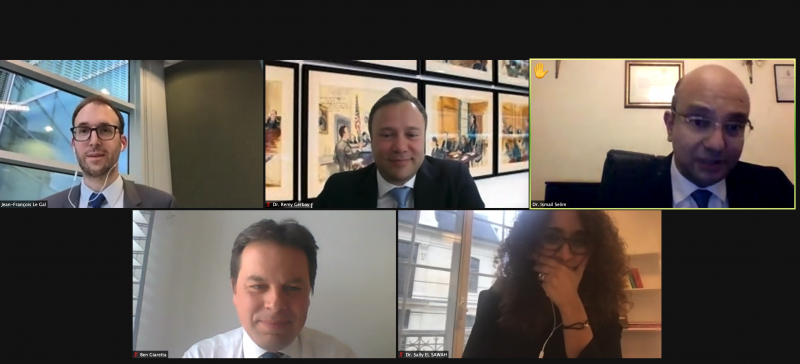

The panel of distinguished speakers included Dr Ismail Selim MCIArb (Director of The Cairo Regional Center for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA) and Vice-Chair of CIArb Egypt), Jean-François Le Gal (Partner at Pinsent Masons LLP), Dr Sally El Sawah (Founding Partner & Principal of El Sawah Law) and Dr Rémy Gerbay (Partner at MoloLamken LLP and Co-Director of an LL.M. in arbitration at QMUL).

The conversation started with Ismail introducing the speakers and explaining how the cooperation between the Egypt and London Branches resulted in this joint event focusing on the “disease” of due process paranoia in international arbitration.

Jean-François opened the discussion with a question about who should be blamed for the procedural paranoia, and he invited the audience to voice their opinion via a poll. The poll asked whether the paranoia can be blamed on arbitrators, parties, counsel, arbitral institutions, all of these players or none of them.

The results were as follows: 35% blamed the arbitrators, 8% the counsel, 6% arbitral institutions, 46 % all of them and 6% none of them.

Once vox populi had been expressed, Jean-François invited the panellists to share their views on the problem.

Speaking from a perceptive on an arbitrator, Sally suggested considering the international nature of arbitration where the parties, counsel, arbitrators and institutions come from different legal backgrounds. In this context, a behaviour which is illegal for one party can be perfectly normal to the other. Arbitrators need to balance these differences, keeping in mind the fundamental principles of arbitration such as party autonomy and a tribunal’s duty to respect parties’ legitimate expectations.

Ismail presented an institutional point of view, referring to the fact that parties often confuse the role of an arbitral institution with that of an arbitral tribunal. When faced with strongly worded letters from the parties, the institutions need to respect their users, act impartially and give all parties equal chances to respond.

Having heard the perspectives of an arbitrator and an institution, Jean-François turned to Rémy to ask whether it is the counsel who can be blamed for procedural paranoia.

Rémy replied that counsel and parties can undoubtedly be blamed for deploying guerrilla tactics, but when it comes to due process paranoia it is the arbitrators who are responsible. The problem lies with arbitrators who are making decisions that are needlessly cautious instead of being robust. He compared it to a person lying in bed at night and who is worried by the sound of a police helicopter flying over their house. In this example, the police can hardly be blamed for that person’s concern. By analogy, the problem with procedural paranoia lies with the tribunal’s assessment of the situation.

Jean-François asked the panellists whether the situation with procedural paranoia had deteriorated over the last few months given the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic. Have counsel deployed new tactics in the pandemic, and what has been the reaction of the other players?

Focussing on the commencement stage, Ismail gave examples of some trends faced by CRCICA, including situations where claimants were trying to commence proceedings without paying the fees, giving the excuse of economic distress. Another example was when parties asked to pay their initial arbitration costs in instalments. Sometimes, the institution had to be pragmatic and flexible to accommodate the needs of the parties.

Sally added a couple of problems faced by arbitrators early in the pandemic, such as anti-suit injunctions, risk of parallel proceedings and difficulties with claimants facing liquidation. At a later stage of the case, the tactics that have been deployed have included parties raising new points and claims at an advanced stage of the proceedings.

Echoing Sally’s example of parties introducing fresh evidence and making new submissions late in the proceedings, Jean-François opened the second poll to the audience. What should happen in the circumstances where there is an agreed timetable, and one party decides to file a new late submission, contrary to that timetable? Should the tribunal admit or reject this? The audience voted 60% for and 40% against, which demonstrated a mix of approaches among participants.

Ismail shared a “war story” of a guerrilla tactic used by a party in a CRCICA arbitration. It involved a claimant who prolonged the proceedings by appointing co-arbitrators who subsequently resigned, and repeating that cycle four times in order to delay the case. CRCICA stepped in and decided it would not grant that claimant a right to appoint a co-arbitrator for the fifth time. An institution needs to be robust in such circumstances.

Another important area in which parties often invoke due process is the claim for a right to in-person hearings.

Ismail gave several solutions that tribunals administered by CRCICA have used to accommodate requests for in-person hearings. These included limiting the number of in-person participants or stipulating that all attendees must present a recent negative PCR test. He also referred to the Egyptian Court of Cassation decision form 27 October 2020 which in its obiter dictum confirmed that virtual hearings are compatible with Egyptian law.

Continuing the theme of potential solutions to the paranoia, Rémy elaborated on his research on the potential risks of setting aside actions when arbitration tribunals took robust decisions on procedural management. Section 33 of the English Arbitration Act 1996 imposes an obligation on arbitrators to act fairly and impartially and, according to Rémy’s research, not a single decision has been made in which an English court has set aside an arbitral award because of an overly robust decision by the tribunal. This was very similar to the position in the US where it is very rare to have an award set aside because of a procedural decision.

In his final question, Jean-François asked whether there is a vaccine or several vaccines which can be developed to fight procedural paranoia.

In Rémy’s view, tribunals’ decisions are cautious because of perceived enforcement risk. The cure to that would be to provide data such as the IBA Report [1]or the publication on due process paranoia by Klaus Peter Berger and Ole Jensen,[2] which demonstrate that there is very little risk of an award being set aside because of robust and firm management decisions. Another cure would involve a codification of acceptable practices, as was the case with virtual hearings.

Sally added that when parties appoint an arbitrator, they want a robust arbitrator who can handle difficult procedural issues. However, there is no “one size fits all” solution, given the different legal cultures and legal practices. A party’s submission may be a genuine request and not a guerrilla tactic. Overall, an arbitrator must show courage and resilience, and be a decision-maker.

In the last poll, the audience expressed the following views: 20% believed the vaccine for procedural paranoia disease was in sight, 17% predicted that the disease would spread further and 63% thought it would be back and forth in form of waves.

Rémy noted that it is very difficult for arbitrators to avoid this paranoia. The last thing arbitrators want is to have their award set aside, which they believe will impact their reputation and their ability to secure further appointments. An arbitrator’s reluctance to take unpopular procedural decisions can also be explained by evolutionary physiology, according to which the human brain favours safe decisions over risky ones.

Ben Giaretta, Chair of the CIArb London Branch, concluded the webinar and thanked all the panellists, in particular Jean-François and Ismail for initiating this event. He also prised the cooperation between the London and Egypt Branches – which is one silver lining of the pandemic. He reiterated Sally’s point that arbitrators need to show resilience and authority. Continuing the metaphor of the procedural paranoia being a virus for international arbitration, he expressed hopes that although this problem might never be completely eradicated, the arbitration community would find ways to live with it and prosper.

Natalia Otlinger MCIArb

PR Officer at the London Branch of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators

[1] International Bar Association, “Annulment of arbitral awards by state court: Review of national case law with respect to the conduct of the arbitral process” (October 2018) https://www.ibanet.org/MediaHa...

[2] Due process paranoia and the procedural judgment rule: a safe harbour for procedural management decisions by international arbitrator; Klaus Peter Berger, J. Ole Jensen

Clockwise from top left: Jean-François Le Gal FCIArb, Dr Rémy Gerbay ACIArb, Dr Ismail Selim MCIArb, Ben Giaretta C.Arb FCIArb and Dr Sally El Sawah